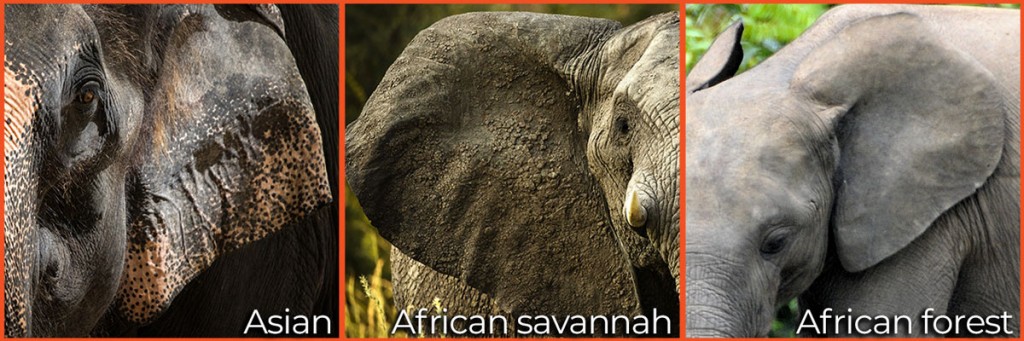

There are three recognized elephant species: Asian, African savannah and African forest. Adult female elephants are called cows; adult males, bulls; and sub adults, calves.

View the full infographic | Download a PDF

Lifespan

Next to humans, elephants are the second longest-living land mammals, with a life expectancy of 65 years compared to a human's 73 years. How long elephants live depends on the threats they face that shorten their lifespan. Elephants in the wild risk losing their lives due to poaching or human conflicts. Elephants in captivity tend to have a shorter life expectancy due to ailments caused by unnatural living conditions.

In the wild, elephants constantly move, migrating as much as 30 miles daily, and are active for 18 hours a day. Lack of space and the opportunity for self-directed exercise for captive elephants not living in natural settings causes muscular-skeletal ailments, arthritis, foot and joint diseases, obesity, and psychological distress. Confinement, resulting in a lack of exercise and long hours standing on hard surfaces are the major contributors to foot infections and arthritis, the leading causes of death among captive elephants.

Species: African Elephants

For centuries it was believed there were only two species of elephants–African and Asian. The African elephant was split into subspecies, the forest, and the savanna. Scientists believed the two were the same species with slightly different populations that mingled on the edges of the forest.

A 2001 study included the first DNA evidence that the savanna elephants and the forest elephants might be a separate species. A subsequent study in 2010 concluded that the two were, in fact, distinct species. A species shares a genetic heritage and the capability to interbreed. DNA from both types of African elephants, the Asian elephant and the extinct woolly mammoth and mastodon (ancient elephant ancestors) showed that the two African elephant species had diverged genetically more than 3 million years ago.

The two African species look very different from each other. African savanna elephants, also known as African bush elephants, are the largest living land mammal in Africa. They have evolved to twice the size of the forest elephant with large pointed and triangular-shaped ears and outward-curving tusks. They range from South to East Africa. The forest elephants, found in dense West African forests, have longer, straighter downward-pointing tusks and rounder ears and are darker than the savannah elephant. The forest elephant has five toenails on its front feet and four on its hind feet, like the Asian elephant. The savanna elephant has four, or sometimes five, on the front feet and only three on the back. The forest elephants live in smaller family groups than the savanna elephants and have a very different diet, with a fondness for fruit when available. Also, they have smoother skin rather than the moisture-collecting deeply wrinkled skin of savannah elephants.

Desert Elephants

Last week we discussed three species of elephants: African forest elephants, African savanna (bush) elephants, and Asian elephants. This week we want to introduce you to the desert elephants found only in the African countries of Namibia and Mali. They are not a separate species or subspecies as once thought but African savanna elephants that have made their homes in the Namib and Sahara deserts. Desert elephants have, however, developed unique traits that allow them to survive an arid climate with temperatures as high as 122 °F / 50 °C surrounded by sand, rocky mountain ranges, and gravel plains. They have a few structural differences from savanna elephants, most notably their thinner bodies and wider feet, enabling them to move more easily across soft sandy terrain. Due to the extreme weather conditions, they roam primarily at night and have adapted their drinking and feeding habits to the available resources. They will walk up to 62-93 miles per day compared to other elephants’ 30 miles a day to feed and find water. They have the largest migration range ever recorded for the species.

Namib, the oldest desert in the world, is almost entirely devoid of surface water with rainfall averaging 1-4 inches annually. The desert elephants, similar to the other animals and plants of the region, absorb moisture from the fog during rainless periods. This allows them to go for several days without water. Like other elephants, they remember the location of water and food across their home ranges and play a critical role in their arid ecosystem by creating paths and digging watering holes.

Although a matriarch and other female elephants typically lead elephant families, the desert elephant families exhibit a looser social structure and are generally smaller than other continental populations. Scientists believe smaller herds are easier to feed, a much-needed survival tactic in a land where food and water sources are scarce.

Subspecies: Asian Elephants

The Asian elephant is one species with three subspecies – the Sumatran, Sri Lankan, and Indian. These smaller groups of a species live in separate regions, have physical and genetic differences, and breed with one another when their territories overlap.

The Sumatran elephant dwells in the lowland forest of Sumatra in Indonesia. There are 2,400 to 2,800 Sumatran elephants left in the wild. They are the smallest of the three subspecies with the lightest skin color and shortest tusks.

Sri Lankan elephants inhabit the dry zone of north, east, and southeast Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka has the highest density of elephants in Asia, with a wild population estimated at 7,500. This subspecies is the largest and darkest of the Asian elephants.

The Indian elephant is native to mainland Asia. As the most widely spread subspecies, they enjoy the greatest range. Their population is thought to be between 20,000 and 30,000., which accounts for most of the remaining wild elephants on the continent.

Keystone Species

Elephants are a keystone species—an animal that plays a unique and essential role in ecosystem functions. The keystone species concept was introduced in 1969 by zoologist Robert T. Paine. A keystone species' role in its ecosystem is similar to a keystone (the top stone in an arch or vault). This final stone is placed during construction and locks all the stones into position, allowing the arch or vault to bear weight. Without it, the structure would collapse. Similarly, elephants are critical for other wildlife. If removed, the ecosystem would change drastically.

Elephants are a keystone species—an animal that plays a unique and essential role in ecosystem functions. The keystone species concept was introduced in 1969 by zoologist Robert T. Paine. A keystone species' role in its ecosystem is similar to a keystone (the top stone in an arch or vault). This final stone is placed during construction and locks all the stones into position, allowing the arch or vault to bear weight. Without it, the structure would collapse. Similarly, elephants are critical for other wildlife. If removed, the ecosystem would change drastically.

Elephants' nomadic behavior—the daily and seasonal migrations through their home ranges—is central to their keystone species classification. As landscape architects, elephants create clearings in the forest as they move about, preventing the overgrowth of certain plant species and allowing space for the regeneration of others. This in turn provides sustenance to other plant-eating animals. When elephants eat plants, fruits, and seeds, they release the seeds in their feces as they travel, often up to 30 miles a day. This distribution of various plant species creates biodiversity which is healthy for an ecosystem. For some plants, this is the only way their seeds are spread. Elephant dung nourishes plants and animals and acts as a breeding ground for insects. During the dry season, elephants use their tusks to dig holes for water to drink, bathe, and socialize with other elephants, which benefits other wildlife. Even their large footprints are instrumental in the life cycle of others as they fill with water when it rains and help smaller creatures survive.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Skin

Elephant’s outer skin layer is about 50 times as thick as a human’s and ranges from one-tenth of an inch to one inch in thickness. However, it is highly sensitive everywhere but especially sensitive in the armpits, the groin region, behind the ears, and around the eyes.

Elephant’s outer skin layer is about 50 times as thick as a human’s and ranges from one-tenth of an inch to one inch in thickness. However, it is highly sensitive everywhere but especially sensitive in the armpits, the groin region, behind the ears, and around the eyes.

To protect their skin from sunburn, repel bugs and guard against overheating, elephants bathe, plaster themselves in mud, and throw dirt on themselves (referred to as dusting). Natural wrinkles in their skin help retain moisture while allowing excess heat to escape.

Whereas humans have hair to keep us warm, elephants’ hair helps keep them cool. Elephants’ sparse hair aids in regulating their body temperature. The hair acts as pin-shaped cooling fins, which work to keep them comfortable by creating more area to release heat and push it away from their bodies.

It is imperative that all captive elephants have free-choice access to a water source and scratching surfaces such as trees to prevent overgrowth of dead skin and avoid blocked pores, dry skin, and infection of their hair follicles.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Hair

Elephants have sparse hair distributed unevenly on their body, with the most noticeable concentrations on top of their head, trunk, and tail.

The hair of most mammals works like an insulator covering their skin to keep them warm in cold weather. However, in the case of elephants native to warm climates (Asia and Africa), body hair brings the opposite effect. Since elephants do not sweat like humans, their sparse pin-shaped hairs help regulate body temperature by acting as cooling fins to release heat. Their long eyelashes and sharp stubbles of hair around their nostrils at the end of their trunk help keep particles and germs from invading the elephant's body. The hair at the end of their trunks is super sensitive, almost like a cat's whiskers. They can use these hairs to locate food and sense where the rest of the herd is so they can stay close to their mother when needed. The tail hair is composed of keratin which is quite different from the hair on the rest of their bodies. It grows in parallel rows along the edges of the tail and can reach lengths up to 3 feet. One of the main reasons for an elephant's hairy tail is to slap and flap away bugs, such as flies.

Much like humans, who have different types, colors, and lengths of hair, elephant hair is unique from one individual to another. Asian elephants have more hair than African elephants, and baby elephants have more hair than adult elephants. Baby Asian elephants have the most hair, which is dark reddish-brown. Elephants, like humans, grow and lose hair with age.

Important Body Parts: Elephant Heart

Elephants have an abnormally shaped heart with wide, thick blood vessels able to withstand higher pressure. Most mammals, including humans, have a single point at the base. Elephants have a double-pointed base so the organ is more circular than heart-shaped. This trait is shared with sirenians which are large plant-eating marine mammals like the manatee and dugong.

The average weight of an adult elephant’s heart is 12-21 kg (26-46 lb) which beats 28-30 times a minute. By comparison, humans have a resting heart rate of 60-100 beats per minute. Unlike many other animals, the elephant’s heart rate speeds up slightly when they lie down. When resting on their side, the sheer weight of the elephant’s body reduces its lung capacity, and to compensate, both the heart rate and blood pressure increase.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Ears

The elephant’s ear acts as a cooling system. When elephants flap their ears in hot weather, large blood vessels on the back of their ears increase heat loss.

African elephants have large ears, shaped much like the continent of Africa itself. The larger surface area of their ears helps to keep African elephants cool in the blazing African sun.

Asian elephants have less to worry about heat-wise, as they tend to live in cool jungle areas, so their ears are smaller.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Eyes

Elephants' eyes are about 1.5" in diameter, only slightly larger than the 1 inch diameter of a human’s. An elephant’s eyes are located on either side of their head, allowing for peripheral vision rather than binocular vision. This allows them to see at an angle rather than a central view. Their range of vision is only about 30 feet, making them somewhat nearsighted.

In addition to upper and lower eyelids, elephants have a third eyelid that moves horizontally across the eye to protect and moisten when they are bathing or dusting. Some elephants develop a white ring that encircles the iris as they mature. This ring is similar to an age-ring humans may develop (as they age) called arcus lipoids which does not affect vision. Elephants' eyelashes, which can grow up to 5 inches long, keep foreign matter out of their eyes.

Elephants have dichromatic vision, the state of having two types of functioning color receptors (cone cells) in their eyes—red and green. Humans have trichromatic vision because we have three kinds of cones: red, green, and blue. However, color-blind humans, like elephants, can see blues and yellows but cannot distinguish between reds and greens. Elephants also exhibit arrhythmic vision. That is, their vision changes with the time of day. At night, their eyes are most sensitive to violet light, so they can see rather well under the smallest amount of daylight when the dominant color of the atmosphere is in the violet range. This allows for activity and travel in the darkest hours of the evening.

Elephant eyes, like a human’s, come in a variety of colors; the four most common eye colors are dark brown, light brown, honey, and gray. Other tones include blue-gray, gold, brown tones, green and yellow, and one eye of an elephant can be differently colored than the other.

Contrary to popular stories, elephants can't cry because they don't have tear ducts. Without tear ducts, excess fluid from their eyes runs down their cheeks, making them look like they're crying.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Brain

An elephant's skull, parts of which are six inches thick, can withstand the force of tusks, trunk, and head-to-head collisions. The back of the skull is flat and spreads out to create arches that protect the brain in every direction. The cranium is filled with honeycomb-like spaces, which makes the large head relatively light-weight.

The elephant's brain weighs 10 to 12 pounds, whereas the human brain weighs three pounds on average. The cerebral cortex (used for cognitive processing) of an elephant brain has the greatest weight, mass, and volume of all land mammals. An elephant's neocortex is highly convoluted (more brain folds) a trait shared by humans, apes, and some dolphin species. The neocortex is the center for higher brain functions, such as perception, decision-making, and language. In addition, spindle neurons, which appear to play a role in the development of intelligent behavior, are found in the brains of humans, great apes, and elephants. These specialized brain cells are involved in processing emotions and social interaction. Elephants also possess a huge and complicated hippocampus, which is linked to emotion by processing certain types of memory. Their large and distinct temporal lobes are associated with memory storage, which explains their excellent memories and ability to follow migratory paths.

Elephants, human beings, and many of the great apes are born without survival skills and must learn these during infancy and adolescence. Comparing brain size at birth to the size of a fully developed adult brain is one way to estimate how much an animal relies on learning as opposed to instinct. The brain weight of most newborn mammals is 90% of an adult’s, while humans are born with 28% and elephants with 35%. The elephant calf gains survival skills and cultural knowledge under the guidance of his/her mother and herd members, as well as from their own experience.

Important Body Parts: Elephant Lungs

The respiratory system of the elephant is quite exceptional. The elephant is the only mammal without a pleural cavity (the fluid-filled space between the lungs). Connective tissue attaches their lungs directly to the chest wall and the diaphragm. This means breathing depends solely on movement of the chest muscle rather than the ribcage expanding. As a result, if the lungs are constricted, or if there is too much pressure on the chest and diaphragm, they risk suffocating.

One possible reason for this unique physiology is that direct (voluntary) control of the muscles allows elephants to deal with pressure differences when their bodies are underwater, and their trunk breaks the surface for air. This ability also helps elephants suck water through their trunk. Elephants inhale mostly through their trunk, although some air goes through their mouth, allowing them to retain water or dust in their trunk without holding their breath. Elephants will breathe out an average of 310 liters of air every minute.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Trunk

An elephant's trunk is a combination of the nose and the upper lip. The nasal cavity runs the length of the trunk with the nostrils located at the tip. Sensory hairs at the end of the trunk can feel an object’s shape, texture, and temperature. An elephant trunk has over 50,000 individual muscles, a complex network of blood vessels and nerves (compared to 600 muscles in the entire human body), a small amount of fat, but no bones or cartilage. Like the human tongue, the trunk is a muscular hydrostat—a muscle or muscle group that works independently, without bone support. Trunks have incredible strength, flexibility, and dexterity, all properties of muscular hydrostats. Elephants use their trunks to smell, touch, grasp, create sounds, socialize, collect water for drinking, select and manipulate food for eating, and breath, including using their trunk as a snorkel when their bodies are underwater.

After birth, the calves' muscles start to develop, and they must learn to master their trunks. By about 4 months, calves learn to use their trunks to eat and drink. By adulthood, the trunk is large and powerful, weighing close to 300 pounds and 6-8 feet long. An adult male can lift more than 400 pounds and reach branches 20 feet high.

Elephant trunks have "fingers" at the end to grip small objects. African elephants have two fingers, while Asian elephants only have one. An Asian elephant most often curls the tip of its trunk around an item and picks it up in a "grasp" method. In contrast, the African elephant uses the "pinch," picking up objects like a human's thumb and index finger.

To drink, an elephant sucks in and holds as much as 2.6 gallons of water with their trunk and then squirts it into their mouth. Food such as grasses, leaves, branches, and fruit are found by smell. They can pick food with the end of their trunk; grasp with the lower portion of their trunk (the heal); or grab and pull with the lower third of their trunk if grasses are tall and more difficult to retrieve. Next, they use their trunk to place the food inside their mouth where their large tongue pulls it to the back so molars can grind the food.

Elephant's trunks are superior to a bloodhound's nose. They can smell an approaching rainstorm from 150 miles away. By changing the shape and size of their nostrils, elephants can control their vocalizations. Also, they use to spray water on themselves to cool down; and to throw dirt or dust on themselves to protect against insect bites and insulate against the sun. When they sense danger, elephants use their trunk to hit or throw objects at the threat. Elephants often intertwine their trunks with other elephants in greeting, specifically friends or family, much like a human handshake or hug.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Tusks

Elephant tusks are long upper incisor teeth made of the same material as human teeth–dentine with an outer layer of enamel. Tusks appear when an elephant is between one and three years old and grow their whole life. Blood and nerves run through the center and down 2/3rds the length of the tusk. If this part of a tusk is cut or broken, it exposes the nerve and causes serious pain. The core of the tusk becomes infected and can cause the tusk to die. Like human teeth, tusks do not grow back if they are severely damaged.

Both sexes of African elephants can have tusks, but a female's tusks are smaller and thinner than a male’s. African elephant tusks can grow up to 10 feet long and weigh up to 200 pounds, although today, most tusks are smaller. For Asian elephants, only males (bulls) have tusks. Asian females have “tushes” which can usually be seen a few inches beyond the lip line, or when they raise their trunk, or open their mouth. Asian males can have tusks as long as an Africans’, but they are usually slimmer and lighter. The largest recorded was 9 feet long and weighed 86 pounds. Males who are naturally tuskless are called “maknas” and are believed to be more aggressive than those with tusks. Tusk size and shape are inherited.

Elephants use their tusks for various purposes, including grazing, digging, stripping bark, sparring and self-protection. Just as most humans are right-handed or left-handed, elephants also seem to prefer using one tusk more than the other. Their dominant tusk usually shows more wear. Elephants play an important role when they topple trees, create open grass lands, and dig holes to access water. Their actions are key to the survival of other species who share the habitat.

Elephant ivory has been considered a valuable material across cultures and continents for thousands of years. In the 19th and 20th centuries, increasing demand for ivory piano keys, billiard balls, and luxury items led to the elephant population's steep decline.

Today, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, (or CITES), severely restricts the ivory trade. Many countries have banned the sale or importation of ivory, and individuals' attitudes toward ivory items and wildlife have changed. However, with over 30,000 African elephants killed each year, the illegal ivory trade still poses a serious threat to their survival. Poaching is an ongoing problem, and not just for elephants, but for wildlife around the world.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Teeth

An elephant's age can be estimated by looking at his/her teeth. During an elephant's lifetime, s/he grows six sets of teeth–two on each side of the mouth, on the top and bottom. As each tooth wears down from grinding food, a new tooth moves up through the gums to replace the worn one. Each mature tooth can measure 10-12 inches long and weigh 20 pounds. When an elephant fails to eat a balanced diet with enough roughage, their teeth do not wear down properly. This can cause teeth to become impacted and infected.

After their last set of teeth wears down, elephants can no longer chew coarse food. In the wild, they spend extended periods of time in swampy areas where the vegetation is less fibrous. In the past, these marshy areas were believed to be elephant burial grounds, part of a dying ritual, but they are actually where elephants go in old age to survive.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Mouth

Elephants have a large mouth complete with a flexible tongue and four grinding molars. Their tongue can weigh up to 26 pounds and can only stretch out to their short lower lip. Elephants select food by smell, pick it up, and then place it in their mouth with their trunks. They use their muscular tongue to pull the food to the back of their mouth where huge molars grind it. Elephants have two sets of teeth on each side of the mouth, on the top and bottom. During their lifetime, they grow six sets of these teeth. As each tooth wears down from grinding food, a new tooth moves up through the gums to replace the worn one. The teeth form over time in a hollow cavity in the jaw. Each mature tooth can measure 10-12 inches long and weigh 20 pounds.

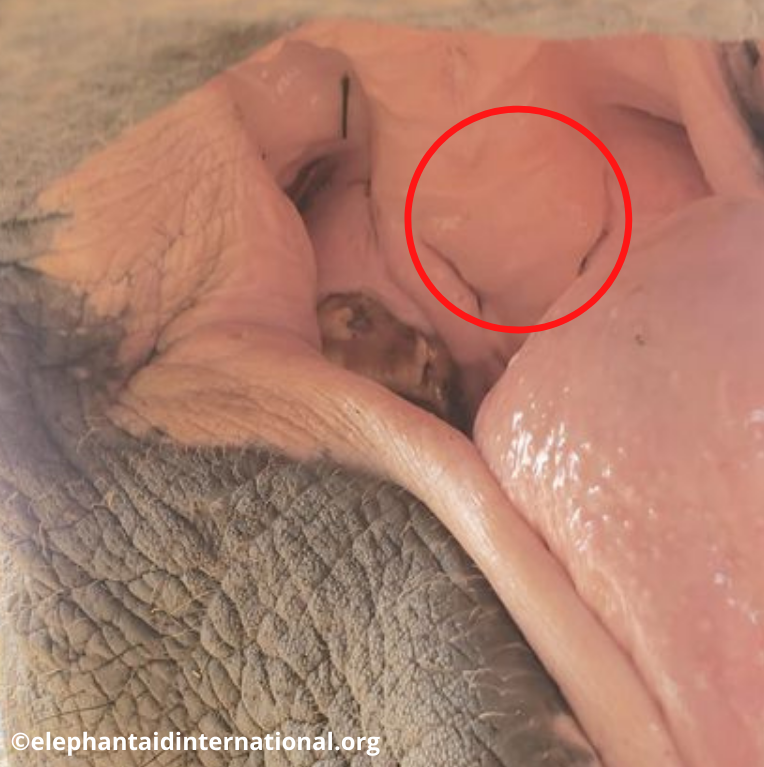

The set of bones that support the tongue and larynx (voice box) is called the hyoid apparatus. Most mammals have nine bones in their hyoid apparatus, but elephants only have five. Fewer bones leave gaps for muscles, tendons, ligaments, and the formation of the pharyngeal pouch just behind the tongue.

The pouch is surrounded by muscles that squeeze the opening, so food passes over and does not contaminate the pouch. This unique design allows elephants to produce infrasound (sounds too low for humans to hear). The pouch can also store up to 1 gallon of clean water. When dangerously overheated, elephants put their trunk deep into their throat to retrieve the water, and then spray it on their head, ears, chest, and back.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Feet

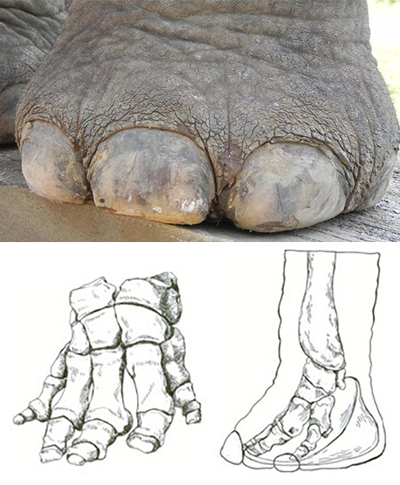

Elephants walk on tiptoe: their toe bones point down so their weight is on the tips of their toes. They have a fatty elastic pad beneath their toes and heel that expands when they put their foot down to absorb shocks and act as a spongy cushion, which enables them to walk silently. They have ridges on the soles of their feet that help them get traction on slippery surfaces.

An elephant foot has 5 toes, but not every toe has a nail. The African forest elephant and the Asian elephant both have 5 toenails on the front feet and 4 on the back feet. The African savanna elephant has 4, or sometimes 5, on the front feet and only 3 on the back. Their footpads and nails continue to grow throughout their lifetime.

Foot health is a serious issue for elephants living in captivity. Inactivity, poor husbandry (animal care) practices, and too much time spent standing and walking on unnaturally hard surfaces such as pavement, hard packed dirt and concrete can cause thin, uneven, and bruised foot pads and cracked nails, leading to infection and osteomyelitis (inflamed bones and/or bone marrow). These diseases have become epidemic among elephants living in captive environments.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Limbs

An elephant's limbs are positioned directly under their body, with bones stacked on top of one another to support their weight. The back legs are slightly longer than the front legs, although the high shoulder makes the front limbs look longer. Unlike most four-legged mammals, an elephant's front leg joints bend backward, like a human’s wrist. The elephant’s wrist is smaller than the foot with both being round shape. The back legs have knees with kneecaps. The rear leg is nearly the same width from the knee down to the foot, while the front of the foot is a little larger than the back (ankle).

An elephant's limbs are positioned directly under their body, with bones stacked on top of one another to support their weight. The back legs are slightly longer than the front legs, although the high shoulder makes the front limbs look longer. Unlike most four-legged mammals, an elephant's front leg joints bend backward, like a human’s wrist. The elephant’s wrist is smaller than the foot with both being round shape. The back legs have knees with kneecaps. The rear leg is nearly the same width from the knee down to the foot, while the front of the foot is a little larger than the back (ankle).

The long bones of the elephant's limbs are spongy and made up of small, needle-like pieces of bone arranged like a honeycomb (instead of hollow parts that contain bone marrow). This feature strengthens the bones while still allowing for blood cell production. Both the front and back limbs can support an elephant's weight, although the front bears sixty percent. An elephant's bones are much wider than most mammals, which gives them a thicker cross-sectional area and makes them more resistant to the type of stresses that can break bones.

Elephants naturally kneel on their wrists, sit on their haunches and lie on their sides. In the wild, elephants walk thirty plus miles a day and can move quickly with top speeds up to 15 miles per hour. This fast gait is not classified as running because all four feet never leave the ground at the same time.

Important Body Parts - Elephant Tail

Elephant tails vary widely due to genetics and circumstance, and like their tusks and ears, their tails provide an excellent way to distinguish them from each other. Elephant tails can be over 4 feet long, and the coarse wire-like hair that grows in parallel rows along the edges of the tail can reach lengths up to 3 feet. The tail hair is predominantly black, but it can be red, brown, or even blond and is composed of keratin which is quite different from the hair on the rest of their bodies.

Elephants have an extraordinary degree of control over their tails. The end of the tail is nearly flat, making it the perfect fly swatter. An elephant may also use its tail to gently feel what is following it, like a baby, or forcefully swat another elephant to indicate they should back off. Elephant tail gestures are a form of communication. The tail of a relaxed elephant hangs down. Fearful, highly playful, or sexually or socially aroused elephants typically raise their tails.

Tail hairs can reveal information about diet, environmental preferences, and location. In Kenya, a study analyzing stable isotopes in tail hair from elephants that wore radio collars to track GPS coordinates revealed what and where the elephants ate. The newest hair growth indicates the elephant's recent diet and environmental conditions, and the older hair further down the tail shows prior diet and environmental conditions. The aim is to better understand their basic need for space.

Jacobson's Organ

The Jacobson's organ, discovered by Ludwig Jacobson in 1813, is also called the vomeronasal organ (VMO) and is part of the olfactory system (sense of smell) of amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. It is used to detect pheromones and chemicals that carry information between individuals of the same species. This patch of sensory cells is located above the roof of the mouth in the main nasal chamber via small slit openings just behind an animal's front teeth.

Elephants release their pheromones in various bodily fluids, such as sweat, urine, dung, and temporal glands (between their eyes and ears) secretions. Capturing the pheromones and transferring them to the VMO is called the Flehmen response. In elephants, this is characterized by moisturizing the finger at the tip of their trunk with nasal mucus, mixing it with another elephant's body secretions, then curling their trunk in their mouth for placement on the roof.

The pheromones can deliver many messages. Male elephants can detect a female's reproductive status, young elephants can instantly recognize their mothers, and herd members can identify moods simply by sampling each other's saliva.

Communication

Elephants have many ways of communicating:

Elephants have many ways of communicating:

Elephant Vocalization: Elephants can produce a variety of sounds from their trunk, mouth, forehead, and chest. These sounds include clicks, purrs, rumbles, snorts, barks, grunts, squeals, groans, trumpets, and roars that can travel through the air up to a mile away. Elephants also produce low-frequency rumbles known as seismic or infrasound, which humans cannot hear. The rumble sends signals through the elephant’s feet and into the ground for up to 30 miles away. Other elephants feel the sounds through their foot pads and are made aware of the location and movement of other elephants. Although humans can’t hear the sounds, we can feel and see the elephant’s forehead and chest vibrate.

Vocalizations originate in the larynx (voice box) and the pharyngeal pouch in their throat. Elephants use more than 70 kinds of vocal sounds which can be gentle and soft, or loud and powerful. Elephants produce different types of vocalization by changing the size of their nostrils as air passes through the trunk. To release a desired sound, it is believed they can hold their head in a certain posture and flap their ears in a particular rhythm and angle to affect the muscles around the voice box to modify a specific call. Researchers have found that females have the largest variety of vocalizations.

Elephants have a wide range of calls for different purposes–to call for help against perceived dangers; warn others about possible threats; coordinate group movements; settle disagreements; show affection; express discomfort, fear, needs and desires; attract mates; and reinforce family bonds. Elephants can distinguish the calls of family members as well as the contact calls of non-related groups.

Body language: Elephants use their body, head, eyes, mouth, ears, tusks, trunk, tail and feet to communicate with each other and other species.

Touch: Elephants are highly tactile, using touch when they play, express affection, reassure, act aggressively or defensively, mate, care for others and explore.

Chemical: Smell is one of elephants’ strongest senses. They pick up smells from the air and the ground, from urine and dung and from other elephants’ genitals, temporal glands and mouths. Males identify when a female is in estrus by scenting her urine. They can identify groups of people who pose a threat to them from their scents and use smell to keep track of family and friends. They can smell an approaching rainstorm from 150 miles away.

How Elephants Detect Danger and Warn Others!

The highly-evolved and intelligent elephant is able to detect danger and send an alert to other members of the herd. Elephants remember threats they’ve experienced even if it has been several years since they encountered them. These dangers include predators, earthquakes and even certain groups of people.

A study with African elephants in Kenya found they were able to detect the scent of the different tribespeople in their area and determine which smells represented people who might hurt them and those who would leave them alone. The men of a tribe called the Masai are known to demonstrate their bravery by spearing elephants. The women of this tribe and both men and women of another local tribe, the Kamba, don’t interact with the elephants so pose little threat to them.

Researchers left clothing that had been worn by members of both tribes. When the elephants encountered the clothing worn by the Masai men they would stampede away until reaching cover. They even showed this defensive behavior when encountering red fabric, the color normally worn by Masai men, even though this fabric had not been worn by anyone at all.

By contrast, they showed little reaction when encountering clothing worn my Masai women or by members of the Kamba tribe.

To warn others of danger, elephants use a wide variety of sounds. They are able to generate frequencies so low the human ear is not able to detect them, but other elephants can actually feel them. The vibrations from the sounds cause slight tremors in the ground that other elephants can feel through their feet even at great distances from the elephant making the sound. This seismic communication works because elephants have incredibly sensitive feet.

This ability to feel slight vibrations in the earth also allows them to detect earthquakes well in advance so they can move away from the area of impending danger.

Elephant Hearing

Like most large mammals, elephants specialize in low frequency hearing due to their long ear canals, wide eardrums, and spacious middle ears. Elephants cannot detect high-frequency sounds as well as mammals with narrow spaced ears, however, they can recognize who is making airborne calls from approximately one mile away. Elephants can differentiate between the calls of family members and non-related groups.

Elephants' ability to detect seismic or infrasound from other elephants is due to their physical design. Elephants and their relatives the dugongs and manatees are mammals, but their cochlear (the hearing part of the inner ear) has evolved to be more like a reptile. Since reptiles' cochlear construction makes them keenly sensitive to vibrations, some believe the similar structure in elephants means they may detect vibrational signals too. The elephant's middle ear also hears low-frequency sounds, and their large eardrums minimize any interfering background noise. The large space between their ears and extending them away from their heads helps elephants excel at identifying the direction and distance of a sound.

Elephant sound waves carried through the air and ground reach different distances. Their ears and feet send and receive communications and can tell the direction, distance, and message content. Research has shown that some infrasound ground vibrations reach the brain's hearing centers in elephants through a process called “bone conduction”. The vibration message travels through the elephant's skeleton directly to bones in the inner ear, bypassing the eardrum altogether.

Sleep

In captivity, adult elephants can sleep 4 to 6 hours a day; in the wild they rest only about two hours and, if necessary, can go several days without sleep. Infants tend to sleep often and in short intervals.

Elephants can doze while standing but must lie down to sleep more deeply. In the coldest months herds favor a south facing location where they benefit from the radiant affect of the sun. When recumbent, they position their front legs near their chest and tuck their trunk under their chin. While in a deep sleep they snore. Herds can be found with one or more members standing watch while others sleep.

Elephants prefer a soft sleeping surface. Unnaturally hard surfaces such as hard pack dirt and concrete cause discomfort and pressure wounds. The preferred substrate for indoor enclosures is estuary sand. Round edges, the physical property of estuary sand, is preferred to other types of sand with straight edges which cause the grains to lock together and become an unnaturally hard surface like concrete.

Walking

An elephant's limbs are positioned directly under the body with bones stacked vertically on top of one another to support their weight. Opposite of most four-legged mammals, an elephant’s front leg joints bend backwards, like humans.

Elephants are built to move walking tens of miles a day. They will walk more than 300 miles to get to water. African savannah elephants walk for 4 months every year, walking at dusk when temperatures are cooler.

Unlike horses who have three gaits, elephants have only one and can reach top speeds of 15 miles per hour. At this speed, most other four-legged animals are well into a gallop. However, an elephant’s gait does not meet the running criteria because all four feet never leave the ground at once.

Elephant Swimming

Elephants have two big advantages over other mammals who swim: their long trunk and a layer of body fat makes them buoyant. Elephants swim by using all four legs to dog paddle. They swim mostly submerged, holding their head above the water and their mouths below. They use their trunk like a snorkel, holding the tip above water, enabling them to breathe normally. Their buoyancy and ease of breathing combine to allow them to swim as far as 30 miles at a time. When and if they tire, they can roll onto their side and float for a short time before they resume swimming.

Elephant families protect calves by surrounding them when they cross a body of water. Still, strong river currents can sweep young calves away. Most times they float to the bank downstream where the family rejoins them. When a steep embankment prevents a calf from leaving the water, its mother, joined by other adults, will use her head to push the calf from behind, sometimes even picking the calf up with their trunks.

Elephants need to be good swimmers so they can cross rivers and lakes when they migrate. Some experts speculate Asian elephants were able to move from southeast India to Sri Lanka by sea because of their swimming ability.

Elephant Migration

Elephants are migratory by nature. Each year, they generally follow the same routes as their ancestors. Migration distances vary considerably depending on environmental conditions, food and water availability, and dangers. The matriarchs of the herd use their remarkable memory to recall these migratory routes, keeping their family safe as they lead them to ripe feeding grounds with the changing of the seasons.

The routes the elephants travel are called “corridors” and are relatively comparable to our road system, allowing us to find our way from point A to point B. These functionally narrow corridors form vital natural habitat links between larger habitats. In addition, they are critical for other wildlife because elephants are a keystone species since other species in the ecosystem largely depend on them. If elephants were removed, the ecosystem would change drastically.

Over the past several decades, elephant corridors in both Asia and Africa have eroded due to deforestation, human infrastructure, village expansion, mining, and the use of electric fences to protect crops, thereby disrupting elephants’ natural pathways. As elephant corridors continue to disappear, human-elephant conflicts become more common—ruining crops, destroying homes, and causing tragic accidents for members of both species.

Elephants are known to prefer the path of least resistance. A recent Kenya study found that elephants do their utmost to avoid going uphill, ignoring prominent hills for flatter paths known as land corridors.

In the early 2000s, conservation groups started to understand elephant migrating behavior and began working to reestablish and protect the previously blocked corridors. Today, information obtained by tracking collars is invaluable in the quest to fully understand elephant migratory behavior and protect the last free-roaming elephants.

Elephants and Cold Weather

Elephants evolved to live in warm climates. African elephants live on savannas and in woods, mountains, and tropical rainforests; Asian elephants in tropical forests. Like all mammals, elephants can heat and cool their bodies from the inside, even when the temperatures outside are very different (a process called thermoregulation). To do this, elephants lie down in a sunny location for a few hours in the afternoon, stay active at night, and then release the heat they stored from their afternoon nap to warm themselves as the temperature plummets. However, since they are still susceptible to cold weather, wild elephants will migrate to a more comfortable climate.

Elephants are not well-suited for most North American winters. The Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA) Standards for Elephant Management and Care state: “That elephants exposed to temperatures below 40°F (5°C) for longer than 60 minutes must be monitored hourly to assess the potential for hypothermia and access to indoor barn stalls or other options for thermal management must be provided for the elephants.”

The need to keep captive-held elephants indoors in cold weather limits their movement and can lead to arthritis, osteoarthritis (loss of joints and bone), skin conditions, weight gain and boredom. Too much time spent standing, walking and sleeping on unnaturally hard surfaces such as concrete, pavement and hard-packed dirt can lead to crippling foot infections, life threatening osteomyelitis (inflamed bones and/or bone marrow) and sores on bony joint areas such as wrists, cheeks, hips and shoulders.

Elephants and Hot Weather

Elephants do not perspire like humans so they must adapt when temperatures soar. To cool themselves, elephants bathe, plaster themselves in mud and throw dirt on themselves (known as dusting), reduce physical activity and stand in the shade.

Their bodies can also control temperature using the natural wrinkles in their skin to help retain moisture while allowing excess heat to escape. Deep wrinkles increase the amount of skin surface which makes this cooling mechanism effective.

Elephant's hair is sparse and helps regulate body temperature. The pin-shaped hairs act as cooling fins to release heat. In the past, a blow torch was used to burn hair from an elephant’s body to make removing dirt and hay before performances fast and easy. This practice resulted in burns and destroyed an important natural heat releasing function.

Elephant's ears also act as a cooling system. An elephant can pump all of its blood through the veins in the back of the ears every 20 minutes. Additionally, flapping the ears or spraying dust, mud, or water on the back side of their ears, cools the blood in the capillaries, which then carries cooled blood back through the body.

Most amazingly, elephants have a reserve of clean water that they retrieve by putting their trunk deep into their throat. When dangerously overheated, they use this reserve to cool their body by spraying it on their head, ears, chest, and back.

As temperatures rise, elephants are unable to release all the heat they absorb and must store the excess heat in their core. When outside temperatures drop overnight, elephants dump their stored body heat thereby preventing heat stress.

Diet

Elephants are herbivores who eat 100 to 200 lbs of plant material each day. In the wild they spend close to 20 hours a day searching for, selecting, collecting and eating a wide variety of live vegetation.

Young elephants learn from their mothers and other elephants what is good for them to eat. African elephants browse, eating mostly grasses in the wet season, adding leaves, twigs, tree bark and branches in the dry season. Asian elephants graze, eating a range of plants, including bamboo in the growing season and adding tree branches in the dry season. Consuming tree bark and branches provides much needed minerals to the elephants' diet.

Nature’s gardeners

The elephant is a keystone species because of its role in the healthy functioning of an ecosystem. Elephants are called nature’s gardeners due to how they change landscapes by digging waterholes, creating footpaths, opening up habitats and dispersing seeds in their dung. Their bodies use only about 50 percent of the food they eat so their manure is rich in nutrients. Calves eat adults’ dung because it has bacteria that help break down the cellulose in the grass they eat.

Drinking

Elephants drink 30 to 50 gallons of water a day, using their trunk like a straw, drawing in up to 10 gallons of water at a time. Their strong trunk muscles stop the water before it reaches their sinuses. Then they place the tip of their trunk up to their mouth and squirt the water into their mouth.

Calves are dependent on their mother's milk for 2 years but will nurse until they are 3 to 4 years old. They drink up to 3 gallons of milk a day!

Elephants living in the wild go to water holes or lakes in the early morning and in the evening at dusk, often bathing at the same time. During winter, they may drink only once, in the middle of the day. If they must, elephants can go a few days without water. When they reach a water source, if it is underground they can use their feet and tusks to dig wells.

Elephant Digestion

Elephants are non-ruminant (one stomach) herbivores. Adults eat 100 to 200 lbs of plant material each day. Elephants, horses, and all other non-ruminant herbivores do not have multiple stomach compartments or chew their cud, as do ruminant mammals like the cow.

The stomach of an elephant is quite different than a human. Rather than being the primary digestion site, it is mainly a food-storage area that is roughly cylindrical and can store between 8 to 18 gallons of food in a full-grown adult. Elephants have a hindgut fermentation system, in which most of their food ferments in the cecum, the spot between the small and large intestine. The food then travels through the large intestine until all the moisture is sucked out. Despite the process lasting up to a day, half of their food intake goes undigested and ends up as a nice pile of uniform dung.

Elephants' inefficient digestion system is one reason they are an integral part of the ecosystem. Their manure is rich in nutrients; seeds and other vegetation passes though in a relatively untouched state, to the benefit of their calves, dung beetles, and birds who feed off it. Frogs live under it, mushrooms grow from it, and some plant species will only sprout once their seeds have been processed and deposited in elephant dung!

Life Stages

The life cycle of elephants occurs in 3 major stages: infancy, adolescence and adulthood. Like humans, each stage lasts for an extended period of time and includes distinct developmental milestones marking each level of maturity.

The Infant Stage:

Elephant infancy is identified by the physical appearance and emotional level of a calf and its dependency on others in the herd for survival. After being in the mother's womb for about 22 months (the longest gestation period in mammals), calves are vulnerable and have a great deal to learn. This stage lasts from birth until the elephant has been weaned off its mother’s milk.

Elephant infancy is identified by the physical appearance and emotional level of a calf and its dependency on others in the herd for survival. After being in the mother's womb for about 22 months (the longest gestation period in mammals), calves are vulnerable and have a great deal to learn. This stage lasts from birth until the elephant has been weaned off its mother’s milk.

Calves begin the weaning process in their first year of life and may continue to be weaned until their tenth year, or until another sibling is born. For the first 3 to 5 years, most calves are totally dependent on their mothers for their nutrition, hygiene, health and security. Forced weaning in captive situations disrupts a calf’s natural development and can result in emotional trauma that can plague the elephant for the remainder of his/her life.

Research suggests that a calf is born with a fairly underdeveloped brain and that, similar to humans and many of the other great apes, most brain development occurs outside the womb. The calf gains survival skills and cultural knowledge under the guidance of his/her mother and herd members and from experience.

The Adolescent Stage:

An elephant’s adolescence extends from the time s/he is weaned (5 to 10 years of age) until about the age of 17. It’s the period in which an elephant’s greatest physical growth and mental maturation take place.

An elephant’s adolescence extends from the time s/he is weaned (5 to 10 years of age) until about the age of 17. It’s the period in which an elephant’s greatest physical growth and mental maturation take place.

It is during this stage that the elephants reach sexual maturity. Males begin to experience musth between the ages of 15 and 18 years of age, which typically reoccurs once a year. Adolescent females feel the first stirrings of maternal instincts. They begin to take keen interest in newborn elephants (called allomothering), gaining practice for when they have newborns of their own.

It is during adolescence that males begin to be pushed from the matriarchal herd. They then join loosely held groups of peers, known as “bachelor pods.”

Females, on the other hand, remain with their mother in the matriarchal herd their entire lives.

The Adult Stage:

Elephants are considered adult starting at around 18 years of age. According to science a male is considered independent when he spends less than 20 percent of his time with his birth family. For some elephants that is as young as nine and for others it is as late as 18 years old. A female elephant will remain with the matriarchal family assisting with nursing and caring for calves.

Elephants are considered adult starting at around 18 years of age. According to science a male is considered independent when he spends less than 20 percent of his time with his birth family. For some elephants that is as young as nine and for others it is as late as 18 years old. A female elephant will remain with the matriarchal family assisting with nursing and caring for calves.

Although sexually mature in their early teens, female elephants generally don’t engage in breeding behavior until their late teens. Researchers believe the female elders control breeding activity in the youth of their herd. Female elephants can reproduce into their 50’s. Over her lifetime an elephant usually produces 5 calves, in 5 year intervals. There is a 1% chance of twinning. Although growth in height has slowed by the age of a female's first calf there is still potential for a female to grow an additional 50-70 cm in height. Scientist believe that like humans, female elephants experience something similar to menopause.

Once independent, adult males spend the majority of their time solitary or in the company of a few other males. Since males continue to grow in height and weight throughout their lives, older males are larger and generally dominant to younger males. When a male is in his late teens or early twenties he typically comes into musth, a natural condition of increased testosterone levels and heightened sexual activity and aggression. The length and intensity of a male's musth period increases with age and is experienced his entire adult life. In a captive situation elephants who receive a rich diet while being confined can experience unnaturally extended and multiple musth periods in one year.

The average life span of an elephant is about 70 years. In captivity, however, elephants tend to have a shorter life expectancy due to ailments caused by lack of autonomy, improper diet, social isolation, confinement to small spaces and spending too much time standing on hard surfaces.

After a lifetime of raising calves, imprinting on young bulls, teaching their descendants, and molding migration routes elephants grow old. Throughout life, elephants will have worn through 6 sets of molars. With their last set of molars gone, elephants find it difficult to feed, become weak, dehydrated and die. Many times their remains are found nearby a water source where they spent their final days eating the soft grasses that grow in and around the water.

Social Structure

Elephants have one of the most closely knit societies of any living species, organized into birth families, bond groups, clans and independent bulls. Their society is fission-fusion: groups come together to socialize and exchange information, then disperse.

Elephants’ ability to form lifelong bonds extends to their relationships with other species. Elephants who are separated from their family as calves will bond with their caregivers and other species of animals.

The Elephant Matriarch

The female who leads elephant family groups is called the matriarch, She is usually the oldest, most respected female, and has proven her wisdom and leadership abilities over time. She is usually also the daughter of the previous matriarch, indicating that leadership abilities pass from generation to generation.

The female who leads elephant family groups is called the matriarch, She is usually the oldest, most respected female, and has proven her wisdom and leadership abilities over time. She is usually also the daughter of the previous matriarch, indicating that leadership abilities pass from generation to generation.

The matriarch is the hub of a complex social network and is crucial to the wellbeing and success of her family. She nurtures strong bonds among her family members, balancing the needs of the group with the need to travel to food and water resources. This cohesiveness is crucial in crises, such as droughts, when the other elephants rely on her to make life-and-death decisions about when and where they’ll migrate.

A wise, experienced matriarch gives her extended family a survival advantage over families led by younger, less experienced females. She determines who is in her family’s social network, keeps her family out of danger and teaches the females how to care for their offspring.

When the matriarch dies, her oldest daughter usually succeeds her.

The Bull

Male elephants are born into a matriarchal society, a female-dominated world of mothers and maternal helpers.

From a young age, male elephants seem to gravitate toward other males of similar ages. As they play, they test their strength, build self-knowledge and acquire skills they will need as they age.

Males leave their birth families at an average age of 14, but they don't leave family life altogether. Instead, they move off and join another family, or move from family to family.

Bulls spend 80% of their time with family groups until the age of about 25. Each new herd is less welcoming to the newcomer than his birth family’s herd. The bull eventually leaves family herds altogether and moves into the loosely held social network of bulls, which are likely to be composed of elephants who are genetically related to each other.

Although the bonds between males are looser and more random than those of females, bulls also have friends and serve as leaders and teachers.

The oldest males seem to have the strongest influence on the cohesion of the herd. Younger males go off on their own for long periods of time, exploring and going from one bachelor herd to another. The older bulls, however, are more likely to encourage interactions among the younger bulls who are with them.

Older bulls also act as teachers and leaders within the herd. For example, older bulls will often get down on their knees to play-fight with the younger males, demonstrating their understanding that adolescents are learning and acquiring life skills from their interactions

Elephant Family

Elephants have one of the most closely knit societies of any living species, based on the birth family. Birth families belong to bond groups and extended clans.

Asian family groups usually number 6 to 7; African, 8 to 10. An elephant family consists of one or more related adult females and immature offspring, led by the matriarch, who is usually the oldest and most respected female. Mothers, daughters and sisters usually stay together all their lives. Males leave the family group when they are about 10 years old, cycling in and out of loosely held bachelor herds.

Family members show extraordinary teamwork and are highly cooperative in group defense, resource acquisition, offspring care and decision-making.

Close family ties are crucial to birth and childcare. A pregnant elephant’s mother and sisters support her during the birth and help raise the calf. Younger female family members act as allomothers, practicing their nurturing skills by babysitting the calf.

Like humans, elephants form deep, long-lasting bonds with their friends and families. Elephants who are separated from their family as calves and forced into captivity will also bond with their human caregivers and other species of animals.

Elephant Bond Groups

As tight-knit as they are, if an elephant family gets too large, it can split in two. It’s smart because both families can forage more effectively if they split up and explore different territories.

As tight-knit as they are, if an elephant family gets too large, it can split in two. It’s smart because both families can forage more effectively if they split up and explore different territories.

Typically, such a split would take place between cousins, and usually not sisters or mothers and daughters. These split families, or “bond groups” may include as many as five or more families, and up to 50 or more individuals. The related groups will continue to associate and occupy the same home range, staying within a mile of each other and keeping in touch through rumbling calls.

Although the ties between individuals across the bond group are weaker than those within a family, bond group members also have close and friendly ties, form alliances against aggressors, assist in the care of another's offspring, defend one another in times of danger and greet one another in a special way.

The cohesiveness of these groups is dependent on the personalities of the individual members and how closely related they are. Most important, the strength of the matriarch's leadership will influence the nature of the relationships among members of the bond group.

The Elephant Clan

The elephant clan is defined as those families who share the same dry season home range (foraging areas when resources are in scarce supply). A clan can include several hundred elephants and can be identified by how its members interact with each other. During times of plenty, several clans may gather to share bountiful food and a lively social life.

African savanna elephants typically live in larger family groups than either of the two other elephant species (African Forest and Asian), and they are more often found in large aggregations.

Reproduction

Elephant Musth

Musth is a Sanskrit word meaning intoxicated. Male (bull) elephants experience musth annually. It is a natural condition of increased testosterone levels and heightened sexual activity and aggression. When a male is in his late teens or early twenties, he typically comes into musth for the first time. The length and intensity of a male's musth period increases with age and is experienced his entire adult life. In a captive situation, elephants who receive a rich diet while being confined can experience unnaturally extended and multiple musth periods in one year.

Both male and female elephants have two temporal glands—one between each eye and ear. These multi-lobed sacs are modified sweat glands that produce Temporin, an oily substance containing proteins and lipids, which both males and females can secrete in times of joy or distress. However, when males enter musth, they discharge a thicker tar-like matter with a strong odor that creates dark streaks down the sides of their face. During musth, their temporal glands swell and press on their eyes, causing pain and oversensitivity to noise and movements. Other behaviors that indicate musth include walking with their head held high and swinging, picking at the ground with their tusks, marking, ear-folding, ear-waving, and urine dripping down the back legs. Males often produce a low, pulsating rumbling noise known as musth rumble which other elephants can hear from great distances. The rumble is often met with reply vocalizations from females in heat. Other males respond differently to the call of a musth male depending upon whether or not they too are in musth. A male in musth moves toward the sound of the call while a non-musth male moves away, avoiding trouble.

Elephant Mating

Female elephants are sexually mature in their early teens but generally, in a wild setting, they do not engage in breeding behavior until their late teens. Females come into estrus (heat), marking ovulation and the ability to become pregnant for only a few days, three times each year. When a male elephant is in his late teens or early twenties, he typically comes into musth, a period of heightened testosterone and aggression when males are driven to mate. However, they do not need to be in musth to mate. Males in musth rank above all non-musth males and therefore obtain more mating than non-musth males. Musth occurs annually in the wild but more often with some captive-held bulls, lasting weeks in wild bulls and in some cases, months in captive-held bulls.

Males need size, strength, and experience to mate successfully. Older males father three-quarters of all calves since females prefer more mature males and reject younger bulls. Bulls in musth travel vast areas searching for females in estrus; this keeps the gene pool varied and strong as direct interbreeding is reduced. Males identify when a female is in estrus by collecting her urine and passing it on to the soft tissue in the roof of their mouth called Jacobson’s organ. The organ is attached to the oral/nasal cavities and primarily functions to detect the reproductive status of a female. This behavior is known as the flehmen response and is characterized by the elephant curling its trunk into its mouth.

Often more than one male will gather around the area of a female in heat, and the most dominant male is the one she lets breed. The male will first pursue the female who may initially avoid this. After some time, she will allow his advances. The bull will gently rest his trunk across the female’s back to signal of his intention to mount. They may mate several times, and he may stay with her until the end of her estrus, warding off other bulls and fighting if necessary (known as mate-guarding). She may, however, mate with others. At the end of estrus, the female returns to her matriarchal herd, and the male leaves in search of other estrus females.

Gestation

Elephant pregnancies last 22 months, the longest of any land animal. Despite continuous research, this slow development of the embryo is not fully understood. Typically, the elephant cow carries one fetus, with only a 1% chance of twins. In the wild, a female can give birth, on average, every five years.

Birth

Most births in the wild occur during the rainy season to ensure the mother has plenty to eat while suckling her calf. Also, wild elephants normally give birth at night to provide them with an undisturbed environment. While the cow prepares to give birth, other female elephants gather around to protect and greet the newborn. Labor pains can last for several days, but the birth itself takes only a few minutes.

The baby elephant, still inside the amniotic sac, drops from the mother’s birth canal to the ground. The mother might blow sand over the calf as she uses her feet or trunk to tear away the sac. To stimulate breathing, she uses her feet to stroke or gently kick the calf. Sometimes cows use their trunks to suck mucous and fluid from the calf’s mouth and trunk. Mothers then consume the afterbirth to avoid detection by predators.

On average, newborn calves stand about 3 feet high and weigh between 170 and 260 pounds. Immediately after birth, the mother and other females help the calf stand and nurse. Since the calf’s trunk is short, it suckles with its mouth. A few hours later, the newborn elephant can walk. Within two days, calves are strong enough to join the rest of the herd, which waits patiently nearby.

Elephant Gender

Aside from the obvious means of identifying gender through genitalia, there are a few other physical traits that help to identify gender.

Mature males are larger than mature females, on average measuring up to 11 feet at the shoulder, while females measure up to 9 feet.

Both African genders have tusks but males grow much longer than females. 11.5 feet is the largest tusk on record.

Asian males have tusks, while females have tushes which resemble tusks but are only a few inches long.

An obvious indication of a male is musth. Mature males experience a season called musth when a thick tar-like secretion called temporin streams from his temporal glands down the side of his face. Less obvious, but noticeable to the trained eye, is the elongated vertical bulge that can be observed on their back side beginning just below their anus.

Females are usually found in herd settings. Those who have nursed a calf at any time during their lifetime will maintain developed breasts which helps to identify her as female.

Also, when tracking an elephant, the gender can be identified by the urine patterns on the ground. When the urine puddle is in front of the elephant’s back footprints, the elephant is male. If the urine puddle is directly between or slightly behind the set of back footprints, the elephant is female.

Intelligence

Self-Awareness

Elephants, along with humans, apes and dolphins, recognize themselves in a mirror, a measure of their self-awareness.

Memory

Elephants are known for their amazing memory which helps them find water during droughts, sites of plentiful food, avoid dangerous places, and recognize other elephants they may not have seen for years.

This information is important to their survival. Scientist think their memory skills are due to their large brain size and to the way their brain is structured. Of all land mammals, they have the largest part of the brain that plays a key role in high brain functions. Along with memory, these functions include the ability to pay attention and understand what they see and hear. They also have more of the part of the brain that is involved in sensing their surroundings, forming complex thoughts, and even language skills.

An MRI study in 2005 showed that elephants have a larger percentage of their brain dedicated to memory functions than even people do. This part takes up 0.7% of the brain in elephants and only 0.5% in humans.

The structure of their brain has been shown to help them live in large groups with other elephants, which is also important for their safety and survival.

Teaching and learning

Elephants must learn the skills they need to survive. They gain the knowledge and survival skills by watching and learning from their mothers, grandmothers, aunts, cousins and others through the years of their childhood and adolescence.

Tool use

Elephants’ intelligence is demonstrated in their tool use. They use branches to swat flies or scratch themselves, and use rocks, logs and their own tusks to disable electric fences. They also use their tusks for offense and defense, to dig, to lift objects and to strip bark from trees.

Emotions

Elephants are known as walking bodies of emotions. In many ways their emotional lives mirror that of humans. They feel the complete range of emotions from happiness and sorrow to pride, anger and jealousy. They are capable of complex thought and deep feeling with emotional attachments not only toward other members of their herd but even toward other species.

They show joy and happiness verbally and physically by bellowing, trumpeting, rumbling and flapping their ears. When greeting another elephant, they will often entwine trunks, click their tusks and lean on each other while rubbing their bodies together.

They show joy and happiness verbally and physically by bellowing, trumpeting, rumbling and flapping their ears. When greeting another elephant, they will often entwine trunks, click their tusks and lean on each other while rubbing their bodies together.

Research suggests that elephants grieve and remember loved ones who have died. They will place branches and clumps of grass over the body of a deceased elephant and acknowledge a passed loved one even many years later by stopping at the place of his/her death.

Their compassion is demonstrated by how they assist sick, injured and young elephants, often slowing their pace when a member of the herd is not able to keep up with the others. One elephant was observed trying to free a baby rhino trapped in the mud. Even though the elephant was charged by the mother rhino she continued working to free the baby.

Unfortunately, they also experience terror, rage and stress after witnessing other elephants being killed.

These intelligent emotional beings with a complex system of familial and social relations thrive due in part to the complexity of their feelings.

Death Rituals and Grief

Elephants are among the few species of mammals other than Homo sapiens and Neanderthals, who appear to have rituals around death. Research suggests that elephants grieve and remember loved ones who have died.

When an elephant in the herd dies, the entire herd mourns its death. As an act of dignity for the dead, elephants will place branches and clumps of grass over the body. They will also vocalize in various ways as they grieve their dead. They may stay with the body for days or weeks at a time. Sometimes a mother will even carry the body of her dead calf with her.

Elephants show a keen interest in bones of their kind, especially those of dead relatives or other elephants they knew. Upon seeing the bones or carcass of another elephant, a family will always stop to investigate them. The ritual generally involves the elephants cautiously extending their trunks, touching the body gently as if obtaining information. They run their trunk tips along the lower jaw and the tusks and the teeth – the parts that would have been most familiar in life and most touched during greetings – the most individually recognizable features. They will acknowledge a past loved one even many years later by stopping at the place of his/her death.

Elephant Relatives

We know elephants are unique, but it might surprise you to learn that the elephant's closest living relative is the rock hyrax, a small, furry herbivore native to Africa and the Middle East. Manatees and dugongs (manatees’ marine mammal cousin) are also closely related to the elephant. (And you thought you had a weird family.)

The elephant, rock hyrax and manatee all descend from a common hooved ancestor from the group of mammals known as tethytheria, who died out some 50 million years ago. That's been long enough for the animals to travel down very different evolutionary paths. Each animal looks and acts quite differently from the others but, nonetheless, they remain closely related.

Hyraxes still have a few physical traits in common with elephants, including tusks that grow from their incisor teeth (most mammals develop tusks from their canine teeth), flattened nails on the tips of their digits and several similarities among their reproductive organs. The little animals live in close family groups, like elephants, but prefer arid, rocky terrain.

The manatees, often called the elephants of the sea, replace their teeth throughout their lives: the older teeth move to the front, fall out and new teeth grow in at the back of their mouth (the same as elephants). Manatees have three or four tiny nails at the end of each flipper, similar to an elephant’s toenails. They also have prehensile upper lips and a shrunken version of a trunk, which they use similarly to elephants, breaking apart vegetation in the water and skillfully steering it to their mouths.

Elephant Ancestors

A Woolly mammoth (left) and an American mastodon (right)

By Dantheman9758 at the English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Mastodons and mammoths look like relatives of today’s elephants but they were different species only distantly related.

All three mammals are members of the order Proboscidea, which is characterized by a flexible trunk formed of the nostrils and upper lip, large tusks, a massive body and columnar legs.

Mastodons were members of the now extinct Mammutidae family. Mammoths and the modern-day elephant are members of the family Elephantidae, which is the only surviving family of the order Proboscidea. Interestingly, the Asian elephant is actually more closely related to the woolly mammoth than to the African elephant.

Mastodons appeared about 27 to 30 million years ago, primarily in North and Central America; mammoths about 5.1 million years ago in Africa. Both species migrated all over the globe, overlapping with each other and then with humans for 2000 years.

Both species stood between 7 and 14 feet (2 meters to 4 meters) tall, and had long, shaggy hair that protected them from the harsh conditions of their respective environments. While similar in size and stature, fossil evidence shows that mastodons were slightly smaller than mammoths, with shorter legs and lower, flatter heads. They were much like modern elephants in three areas: all three had similar digestive systems, needed to eat the same quantities and types of food and had similar tolerance for water shortages.

Mastodons died out 10,000 to 11,000 years ago and woolly mammoths 4,000 years ago due to several factors, including climate change, variations in habitat, disease and human hunting.

The first mastodon fossils were discovered in 1705 in New York’s Hudson River Valley; the first fully documented woolly mammoth skeleton 1799 in Siberia.

In 1850, mastodon bones were found in Wakulla Springs, Florida, less than an hour from Elephant Refuge North America’s current home. The springs are also the winter home for manatees, a close relative of today’s elephant. Appropriately, locals fondly call them the “Wakullaphant.”

Elephant Symbolism

The elephant has a long-standing history in many cultures. It inhabits mythology, religious ceremonies, and popular culture. The earliest recording of elephants dates back to prehistoric rock carvings.

In Asia, the elephant personifies wisdom, and strength, and is the remover of obstacles. In Africa, elephants represent sovereignty, war, royalty, knowledge, and moral and spiritual power. North American natives believed the mammoth (the elephant's ancestor) embodied wisdom, good luck, strength, and energy.

Elephant symbolism is also common among many philosophies and religions. Ganesha, a prominent deity in Hinduism, is depicted with an elephant's head on a human body. He is the god of luck, salvation, prudence, and wisdom. The Buddhist tradition of giving a white elephant as a sign of justice, peace, and prosperity originates from the birth of Buddha, the revered founder of Buddhism. In Christianity, the elephant is an icon of temperance, patience, and virtue. Carl Jung, the founder of analytical psychology, believed elephants in our dreams represent the self.

The belief that elephant figurines are lucky if their trunks are held up is thought to be a North American superstition since there is no apparent origin in Indian or Southeast Asian culture.

Wild Elephant Location and Population